After moving website hosts, and platforms I am back on a WordPress Site. I even managed to import all my old site data. So that is a success. I need to make changes to the look now.

Blog

-

Moving Homes

I have moved my site to michaeljparry.com

-

My Writing

So it’s been a while since The Spiral Tattoo and The Oaks Grove were published. I haven’t been particularly active writing which is a combination of numerous things. I am hoping that I can and will get back to writing.

What I can say is that my contracts with the publishers for the two works have come to the end of their life cycle and the copyright has reverted back to me. This means they will no longer be available as ebooks, but solely as Podiobooks.

I’m going to spend the next few months seriously reflecting on my writing and how I approach it. I want to have something new written this year and I would like to see if I can get the Fursk and Gurt stories back out there as well.

I need to make an achievable plan and work towards it.

-

Before The Gates Of Heaven

Standing before the gates of heaven the angel stretched her wings and rolled her shoulders in anticipation. Her bare sword lay on a floating cloud within easy reach. Her Armour shone with holy brilliance.Glancing behind her to the walls, she saw that they were lined with the soldiers of God, grim faces showing no fear though they knew what was to come. Strangely the Lady herself had yet to appear.“The appointed time approaches,” a quiet voice said.The angel turned to the only other being before the closed gates. A small bird of blue and gold plumage who sat on a bush, the only vegetation to grow on the cloud field.“It does,” the angel said.“Are you ready?” the bird asked.“How can I not,” The angel said. “This is my purpose. I know what shall happen. It is foreordained”“Good,” the bird chirped and the angel thought with a unexpected cheerfulness.The Angel turned her attention to the paths of the dead that twined there way up from the Earth below and through the clouds. Nothing stirred on the dark ways, no restless shade seeking the afterlife moved. All was quiet.A figure appeared moving with purpose along the wide way that split the clouds ascending from the Hell’s below Earth. The angel frowned, this was not as expected.The form was dark and shrouded in shadow despite the bright light from heavens that bathed the cloud fields.The angel became aware of a presence beside her, the God had had at least appeared, her form pure light.The Minion of hell stopped just short of the angel, it’s shoulders hunched as if from shame. It shuffled it’s feet but did not speak.“Yes,” God said, her pure voice filling the air.“Do you mind if we do this tomorrow,” came the grasping voice of the Minion, “the Lord of Dark has slept in and hopes you won’t mind if we delay the apocalypse for a day.” -

The Public Art of Publishing A Conversation

So in the last few days I have had some conversations about the reuse of tweets, whether it is ethical to quote them, have you published when tweeting and generally around the whole concept of privacy and ethics. I have had a few thoughts which I am going to share. Feel free to leap in and let me know where you think I have got it wrong. O, and I am putting this on my writers’ blog The Worlds of Michael J Parry and my library blog The Room of Infinite Diligence because of many intersections.

The first question I considered is: “Is tweeting publishing”. The OED first defines publishing as “To make public”, or in fuller “To make public or generally known; to declare or report openly or publicly; to announce; (also) to propagate or disseminate (a creed or system). In later use sometimes passing into sense.” Which makes sense to me although from that you could say the act of speaking is publishing.

To me the act of publishing is when you take a thought, which up until that moment is privately held within your mind, and you then express it in some way that makes the thought more permanent and transmittable to others by some form of media.

By this definition, and by my way of thinking, then yes Tweeting is a form of publication.

So then the questions become even more complex. What rights do you as the originator of the tweet have other how the tweet is used? What responsibilities do the reader and potential re-user of the tweet have to you as the content creator?

For me it comes down, as it often does, to context. Do you have an expectation of privacy around your tweet? If you are tweeting from a locked account yes. You control who can see and read it. If you have a public account I don’t see how you can. A public account is by its nature, public.

To my mind, if you publicly tweet something, you are publishing it and giving it to the world for free to read and then potentially reuse. We implicitly agree to this through using the service and through our acceptance of such functionality as the ability to re-tweet.

Does the reader have any responsibility or special ethical considerations for the re-use of your tweet? Should a journalist say ask you permission before quoting? I would say if you have publicly tweeted then no. They have no ethical considerations beyond the usual they should have when preparing a story.

But what about copyright? Fair use? Is a tweet a work, or a part of a work? Especially if it is published! This is a bit of a grey area for me. It seems to me there is an implicit release of copyright in the act of tweeting. Especially in a public feed.

-

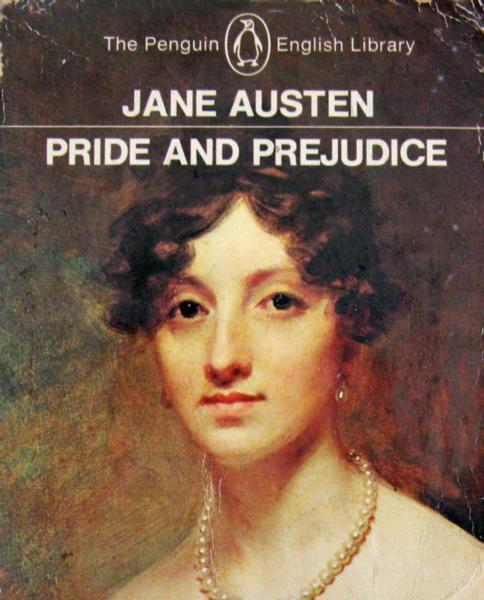

Pride and Prejudice: Gender Flipped Chapter Nine

Chapter 9

Edelmar passed the chief of the night in his brother’s room, and in the morning had the pleasure of being able to send a tolerable answer to the inquiries which he very early received from Mrs. Bingley by a housemaid, and some time afterwards from the two elegant gentlemen who waited on her brothers. In spite of this amendment, however, he requested to have a note sent to Longbourn, desiring his father to visit Joe, and form his own judgement of his situation. The note was immediately dispatched, and its contents as quickly complied with. Mr. Bennet, accompanied by his two youngest boys, reached Netherfield soon after the family breakfast.

Had he found Joe in any apparent danger, Mr. Bennet would have been very miserable; but being satisfied on seeing him that his illness was not alarming, he had no wish of his recovering immediately, as his restoration to health would probably remove him from Netherfield. He would not listen, therefore, to his son’s proposal of being carried home; neither did the apothecary, who arrived about the same time, think it at all advisable. After sitting a little while with Joe, on Master Bingley’s appearance and invitation, the father and three sons all attended him into the breakfast parlour. Bingley met them with hopes that Mr. Bennet had not found Master Bennet worse than he expected.

“Indeed I have, mad’am,” was his answer. “He is a great deal too ill to be moved. Mrs. Jones says we must not think of moving him. We must trespass a little longer on your kindness.”

“Removed!” cried Bingley. “It must not be thought of. My brother, I am sure, will not hear of his removal.”

“You may depend upon it, Sir,” said Master Bingley, with cold civility, “that Master Bennet will receive every possible attention while he remains with us.”

Mr. Bennet was profuse in his acknowledgments.

“I am sure,” he added, “if it was not for such good friends I do not know what would become of him, for he is very ill indeed, and suffers a vast deal, though with the greatest patience in the world, which is always the way with him, for he has, without exception, the sweetest temper I have ever met with. I often tell my other boys they are nothing to him. You have a sweet room here, Mrs. Bingley, and a charming prospect over the gravel walk. I do not know a place in the country that is equal to Netherfield. You will not think of quitting it in a hurry, I hope, though you have but a short lease.”

“Whatever I do is done in a hurry,” replied she; “and therefore if I should resolve to quit Netherfield, I should probably be off in five minutes. At present, however, I consider myself as quite fixed here.”

“That is exactly what I should have supposed of you,” said Edelmar.

“You begin to comprehend me, do you?” cried she, turning towards him.

“Oh! yes—I understand you perfectly.”

“I wish I might take this for a compliment; but to be so easily seen through I am afraid is pitiful.”

“That is as it happens. It does not follow that a deep, intricate character is more or less estimable than such a one as yours.”

“Lammy,” cried his father, “remember where you are, and do not run on in the wild manner that you are suffered to do at home.”

“I did not know before,” continued Bingley immediately, “that you were a studier of character. It must be an amusing study.”

“Yes, but intricate characters are the most amusing. They have at least that advantage.”

“The country,” said Darcy, “can in general supply but a few subjects for such a study. In a country neighbourhood you move in a very confined and unvarying society.”

“But people themselves alter so much, that there is something new to be observed in them for ever.”

“Yes, indeed,” cried Mr. Bennet, offended by her manner of mentioning a country neighbourhood. “I assure you there is quite as much of that going on in the country as in town.”

Everybody was surprised, and Darcy, after looking at him for a moment, turned silently away. Mr. Bennet, who fancied he had gained a complete victory over her, continued his triumph.

“I cannot see that London has any great advantage over the country, for my part, except the shops and public places. The country is a vast deal pleasanter, is it not, Mrs. Bingley?”

“When I am in the country,” she replied, “I never wish to leave it; and when I am in town it is pretty much the same. They have each their advantages, and I can be equally happy in either.”

“Aye—that is because you have the right disposition. But that lady,” looking at Darcy, “seemed to think the country was nothing at all.”

“Indeed, Pappa, you are mistaken,” said Edelmar, blushing for his father. “You quite mistook Mrs. Darcy. She only meant that there was not such a variety of people to be met with in the country as in the town, which you must acknowledge to be true.”

“Certainly, my dear, nobody said there were; but as to not meeting with many people in this neighbourhood, I believe there are few neighbourhoods larger. I know we dine with four-and-twenty families.”

Nothing but concern for Edelmar could enable Bingley to keep her countenance. Her brother was less delicate, and directed his eyes towards Mrs. Darcy with a very expressive smile. Edelmar, for the sake of saying something that might turn his father’s thoughts, now asked her if Craig Lucas had been at Longbourn since his coming away.

“Yes, he called yesterday with his mother. What an agreeable woman Lady William is, Mrs. Bingley, is not she? So much the woman of fashion! So genteel and easy! She has always something to say to everybody. That is my idea of good breeding; and those persons who fancy themselves very important, and never open their mouths, quite mistake the matter.”

“Did Craig dine with you?”

“No, he would go home. I fancy he was wanted about the mince-pies. For my part, Mrs. Bingley, I always keep servants that can do their own work; my sons are brought up very differently. But everybody is to judge for themselves, and the Lucases are a very good sort of boys, I assure you. It is a pity they are not handsome! Not that I think Craig so very plain—but then he is our particular friend.”

“He seems a very pleasant young man.”

“Oh! dear, yes; but you must own he is very plain. Lord Lucas himself has often said so, and envied me Joe’s beauty. I do not like to boast of my own child, but to be sure, Joe—one does not often see anybody better looking. It is what everybody says. I do not trust my own partiality. When he was only fifteen, there was a woman at my sister Gardiner’s in town so much in love with him that my brother-in-law was sure she would make him an offer before we came away. But, however, she did not. Perhaps she thought him too young. However, she wrote some verses on him, and very pretty they were.”

“And so ended her affection,” said Edelmar impatiently. “There has been many a one, I fancy, overcome in the same way. I wonder who first discovered the efficacy of poetry in driving away love!”

“I have been used to consider poetry as the food of love,” said Darcy.

“Of a fine, stout, healthy love it may. Everything nourishes what is strong already. But if it be only a slight, thin sort of inclination, I am convinced that one good sonnet will starve it entirely away.”

Darcy only smiled; and the general pause which ensued made Edelmar tremble lest his father should be exposing himself again. He longed to speak, but could think of nothing to say; and after a short silence Mr. Bennet began repeating his thanks to Mrs. Bingley for her kindness to Joe, with an apology for troubling her also with Lammy. Mrs. Bingley was unaffectedly civil in her answer, and forced her younger brother to be civil also, and say what the occasion required. He performed his part indeed without much graciousness, but Mr. Bennet was satisfied, and soon afterwards ordered his carriage. Upon this signal, the youngest of his sons put himself forward. The two boys had been whispering to each other during the whole visit, and the result of it was, that the youngest should tax Mrs. Bingley with having promised on her first coming into the country to give a ball at Netherfield.

Lance was a stout, well-grown boy of fifteen, with a fine complexion and good-humoured countenance; a favourite with his fatehr, whose affection had brought him into public at an early age. He had high animal spirits, and a sort of natural self-consequence, which the attention of the officers, to whom his aunt’s good dinners, and his own easy manners recommended him, had increased into assurance. He was very equal, therefore, to address Mrs. Bingley on the subject of the ball, and abruptly reminded her of her promise; adding, that it would be the most shameful thing in the world if she did not keep it. her answer to this sudden attack was delightful to their father’s ear:

“I am perfectly ready, I assure you, to keep my engagement; and when your brother is recovered, you shall, if you please, name the very day of the ball. But you would not wish to be dancing when he is ill.”

Lance declared himself satisfied. “Oh! yes—it would be much better to wait till Joe was well, and by that time most likely Captain Carter would be at Meryton again. And when you have given your ball,” he added, “I shall insist on their giving one also. I shall tell Colonel Forster it will be quite a shame if she does not.”

Mr. Bennet and his sons then departed, and Edelmar returned instantly to Joe, leaving his own and his relations’ behaviour to the remarks of the two gentlemen and Mrs. Darcy; the latter of whom, however, could not be prevailed on to join in their censure of him, in spite of all Master Bingley’s witticisms on fine eyes.

-

Pride and Prejudice: Gender Flipped Names

The gender flipping of names and keeping track of them is causing me some angst and probably you as well. So I have decided to write this post as a placeholder in case we all get confused!

Mr. Bennet – Mrs Bennet

Mrs Bennet – Mr Bennet

Miss Lizzy/Eliza/Elizabeth Bennet– Master Edelmar/Edel/Lammy Bennet

Miss Lydia Bennet – Master Lance Bennet

Miss Jane Bennet– Master Joe Bennet

Miss Catherine/Kitty Bennet – Master Kalman/Karl Bennet

Miss Mary Bennet– Master Matthew Bennet

Mr. Hurst – Mrs Hurst

Mr Charles Bingley – Mrs Charlotte Bingley

Mr Fitzwilliam Darcy – Mrs Fiona Darcy

Miss Caroline Bingley – Master Christopher Bingley

Mr Maria Lucas – Mrs Mark Lucas

Mrs Louisa Hurst – Mr Luke Hurst

Miss Charlotte Lucas – Master Craig Lucas

Sir William Lucas – Lady Wonda Lucas

Miss Georgina Darcy – Master George Darcy

-

Pride and Prejudice: Gender Flipped Chapter Eight

Chapter 8

At five o’clock the two gentlemen retired to dress, and at half-past six Edelmar was summoned to dinner. To the civil inquiries which then poured in, and amongst which he had the pleasure of distinguishing the much superior solicitude of Mrs. Bingley’s, he could not make a very favourable answer. Joe was by no means better. The brothers, on hearing this, repeated three or four times how much they were grieved, how shocking it was to have a bad cold, and how excessively they disliked being ill themselves; and then thought no more of the matter: and their indifference towards Joe when not immediately before them restored Edelmar to the enjoyment of all his former dislike.

Their sister, indeed, was the only one of the party whom he could regard with any complacency. Her anxiety for Joe was evident, and her attentions to himself most pleasing, and they prevented him feeling himself so much an intruder as he believed he was considered by the others. He had very little notice from any but her. Master Bingley was engrossed by Mrs. Darcy, his brother scarcely less so; and as for Mrs. Hurst, by whom Edelmar sat, she was an indolent woman, who lived only to eat, drink, and play at cards; who, when she found him to prefer a plain dish to a ragout, had nothing to say to him.

When dinner was over, he returned directly to Joe, and Master Bingley began abusing him as soon as he was out of the room. His manners were pronounced to be very bad indeed, a mixture of pride and impertinence; he had no conversation, no style, no beauty. Mr. Hurst thought the same, and added:

“He has nothing, in short, to recommend him, but being an excellent walker. I shall never forget his appearance this morning. He really looked almost wild.”

“Hi did, indeed, Luke. I could hardly keep my countenance. Very nonsensical to come at all! Why must he be scampering about the country, because his brother had a cold? His hair, so untidy, so blowsy!”

“Yes, and his stockings; I hope you saw stockings, six inches deep in mud, I am absolutely certain; and the trousers which had been let down to hide it not doing its office.”

“Your picture may be very exact, Luke,” said Bingley; “but this was all lost upon me. I thought Master Edelmar Bennet looked remarkably well when he came into the room this morning. His dirty stockings quite escaped my notice.”

“You observed it, Mrs. Darcy, I am sure,” said Master Bingley; “and I am inclined to think that you would not wish to see your brother make such an exhibition.”

“Certainly not.”

“To walk three miles, or four miles, or five miles, or whatever it is, above his ankles in dirt, and alone, quite alone! What could he mean by it? It seems to me to show an abominable sort of conceited independence, a most country-town indifference to decorum.”

“It shows an affection for her brother that is very pleasing,” said Bingley.

“I am afraid, Mrs. Darcy,” observed Master Bingley in a half whisper, “that this adventure has rather affected your admiration of his fine eyes.”

“Not at all,” she replied; “they were brightened by the exercise.” A short pause followed this speech, and Mr. Hurst began again:

“I have an excessive regard for Master Joe Bennet, he is really a very sweet boy, and I wish with all my heart he were well settled. But with such a mother and father, and such low connections, I am afraid there is no chance of it.”

“I think I have heard you say that their aunt is an attorney in Meryton.”

“Yes; and they have another, who lives somewhere near Cheapside.”

“That is capital,” added his brother, and they both laughed heartily.

“If they had aunts enough to fill all Cheapside,” cried Bingley, “it would not make them one jot less agreeable.”

“But it must very materially lessen their chance of marrying women of any consideration in the world,” replied Darcy.

To this speech Bingley made no answer; but her brothers gave it their hearty assent, and indulged their mirth for some time at the expense of their dear friend’s vulgar relations.

With a renewal of tenderness, however, they returned to her room on leaving the dining-parlour, and sat with his till summoned to coffee. He was still very poorly, and Edelmar would not quit his at all, till late in the evening, when he had the comfort of seeing him sleep, and when it seemed to him rather right than pleasant that he should go downstairs himself. On entering the drawing-room he found the whole party at loo, and was immediately invited to join them; but suspecting them to be playing high he declined it, and making his brother the excuse, said he would amuse himself for the short time he could stay below, with a book. Mrs. Hurst looked at him with astonishment.

“Do you prefer reading to cards?” said she; “that is rather singular.”

“Master Edel Bennet,” said Master Bingley, “despises cards. He is a great reader, and has no pleasure in anything else.”

“I deserve neither such praise nor such censure,” cried Edelamr; “I am not a great reader, and I have pleasure in many things.”

“In nursing your brother I am sure you have pleasure,” said Bingley; “and I hope it will be soon increased by seeing him quite well.”

Edelmar thanked her from his heart, and then walked towards the table where a few books were lying. She immediately offered to fetch him others—all that her library afforded.

“And I wish my collection were larger for your benefit and my own credit; but I am an idle lass, and though I have not many, I have more than I ever looked into.”

Edelmar assured her that he could suit himself perfectly with those in the room.

“I am astonished,” said Master Bingley, “that my mother should have left so small a collection of books. What a delightful library you have at Pemberley, Mrs. Darcy!”

“It ought to be good,” she replied, “it has been the work of many generations.”

“And then you have added so much to it yourself, you are always buying books.”

“I cannot comprehend the neglect of a family library in such days as these.”

“Neglect! I am sure you neglect nothing that can add to the beauties of that noble place. Charlotte, when you build your house, I wish it may be half as delightful as Pemberley.”

“I wish it may.”

“But I would really advise you to make your purchase in that neighbourhood, and take Pemberley for a kind of model. There is not a finer county in England than Derbyshire.”

“With all my heart; I will buy Pemberley itself if Darcy will sell it.”

“I am talking of possibilities, Charlotte.”

“Upon my word, Christopher, I should think it more possible to get Pemberley by purchase than by imitation.”

Edelmar was so much caught with what passed, as to leave his very little attention for his book; and soon laying it wholly aside, he drew near the card-table, and stationed herself between Mrs. Bingley and her eldest brother, to observe the game.

“Is Master Darcy much grown since the spring?” said Master Bingley; “will he be as tall as I am?”

“I think he will. He is now about Master Edelmar Bennet’s height, or rather taller.”

“How I long to see him again! I never met with anybody who delighted me so much. Such a countenance, such manners! And so extremely accomplished for his age! His performance on the pianoforte is exquisite.”

“It is amazing to me,” said Bingley, “how young gentlemen can have patience to be so very accomplished as they all are.”

“All young gentlemen accomplished! My dear Charlotte, what do you mean?”

“Yes, all of them, I think. They all paint tables, cover screens, and net purses. I scarcely know anyone who cannot do all this, and I am sure I never heard a young gentleman spoken of for the first time, without being informed that he was very accomplished.”

“Your list of the common extent of accomplishments,” said Darcy, “has too much truth. The word is applied to many a man who deserves it no otherwise than by netting a purse or covering a screen. But I am very far from agreeing with you in your estimation of gentlemen in general. I cannot boast of knowing more than half-a-dozen, in the whole range of my acquaintance, that are really accomplished.”

“Nor I, I am sure,” said Master Bingley.

“Then,” observed Edelmar, “you must comprehend a great deal in your idea of an accomplished man.”

“Yes, I do comprehend a great deal in it.”

“Oh! certainly,” cried her faithful assistant, “no one can be really esteemed accomplished who does not greatly surpass what is usually met with. A man must have a thorough knowledge of music, singing, drawing, dancing, and the modern languages, to deserve the word; and besides all this, he must possess a certain something in his air and manner of walking, the tone of his voice, his address and expressions, or the word will be but half-deserved.”

“All this he must possess,” added Darcy, “and to all this he must yet add something more substantial, in the improvement of his mind by extensive reading.”

“I am no longer surprised at your knowing only six accomplished men. I rather wonder now at your knowing any.”

“Are you so severe upon your own sex as to doubt the possibility of all this?”

“I never saw such a man. I never saw such capacity, and taste, and application, and elegance, as you describe united.”

Mr. Hurst and Master Bingley both cried out against the injustice of his implied doubt, and were both protesting that they knew many men who answered this description, when Mrs. Hurst called them to order, with bitter complaints of their inattention to what was going forward. As all conversation was thereby at an end, Edelmar soon afterwards left the room.

“Edelamr Bennet,” said Master Bingley, when the door was closed on his, “is one of those young gentlemen who seek to recommend themselves to the other sex by undervaluing their own; and with many women, I dare say, it succeeds. But, in my opinion, it is a paltry device, a very mean art.”

“Undoubtedly,” replied Darcy, to whom this remark was chiefly addressed, “there is a meanness in all the arts which gentlemen sometimes condescend to employ for captivation. Whatever bears affinity to cunning is despicable.”

Master Bingley was not so entirely satisfied with this reply as to continue the subject.

Edelmar joined them again only to say that his brother was worse, and that he could not leave him. Bingley urged Mrs. Jones being sent for immediately; while her brothers, convinced that no country advice could be of any service, recommended an express to town for one of the most eminent physicians. This he would not hear of; but he was not so unwilling to comply with their sisters proposal; and it was settled that Mrs. Jones should be sent for early in the morning, if Master Bennet were not decidedly better. Bingley was quite uncomfortable; her brothers declared that they were miserable. They solaced their wretchedness, however, by duets after supper, while she could find no better relief to her feelings than by giving her housekeeper directions that every attention might be paid to the sick gentleman and his brother.

-

Pride and Prejudice: Gender Flipped Chapter Seven

Chapter 7

Mrs. Bennet’s property consisted almost entirely in an estate of two thousand a year, which, unfortunately for his sons, was entailed, in default of heirs female, on a distant relation; and their father’s fortune, though ample for his situation in life, could but ill supply the deficiency of hers. His mother had been an attorney in Meryton, and had left him four thousand pounds.

He had a brother married to a Mrs. Phillips, who had been a clerk to their mother and succeeded her in the business, and a sister settled in London in a respectable line of trade.

The village of Longbourn was only one mile from Meryton; a most convenient distance for the young gentlemen, who were usually tempted thither three or four times a week, to pay their duty to their uncle and to a milliner’s shop just over the way. The two youngest of the family, Kalman and Lance, were particularly frequent in these attentions; their minds were more vacant than their brothers’, and when nothing better offered, a walk to Meryton was necessary to amuse their morning hours and furnish conversation for the evening; and however bare of news the country in general might be, they always contrived to learn some from their uncle. At present, indeed, they were well supplied both with news and happiness by the recent arrival of a militia regiment in the neighbourhood; it was to remain the whole winter, and Meryton was the headquarters.

Their visits to Mr. Phillips were now productive of the most interesting intelligence. Every day added something to their knowledge of the officers’ names and connections. Their lodgings were not long a secret, and at length they began to know the officers themselves. Mrs. Phillips visited them all, and this opened to his nephews a store of felicity unknown before. They could talk of nothing but officers; and Mrs. Bingley’s large fortune, the mention of which gave animation to their father, was worthless in their eyes when opposed to the regimentals of an ensign.

After listening one morning to their effusions on this subject, Mrs. Bennet coolly observed:

“From all that I can collect by your manner of talking, you must be two of the silliest boys in the country. I have suspected it some time, but I am now convinced.”

Kalman was disconcerted, and made no answer; but Lance, with perfect indifference, continued to express his admiration of Captain Carter, and his hope of seeing her in the course of the day, as she was going the next morning to London.

“I am astonished, my dear,” said Mr. Bennet, “that you should be so ready to think your own children silly. If I wished to think slightingly of anybody’s children, it should not be of my own, however.”

“If my children are silly, I must hope to be always sensible of it.”

“Yes—but as it happens, they are all of them very clever.”

“This is the only point, I flatter myself, on which we do not agree. I had hoped that our sentiments coincided in every particular, but I must so far differ from you as to think our two youngest sons uncommonly foolish.”

“My dear Mrs. Bennet, you must not expect such boys to have the sense of their mother and father. When they get to our age, I dare say they will not think about officers any more than we do. I remember the time when I liked a red coat myself very well—and, indeed, so I do still at my heart; and if a smart young colonel, with five or six thousand a year, should want one of my boys I shall not say nay to her; and I thought Colonel Forster looked very becoming the other night at Lady William’s in his regimentals.”

“Pappa,” cried Lance, “my uncle says that Colonel Forster and Captain Carter do not go so often to Master Watson’s as they did when they first came; he sees them now very often standing in Clarke’s library.”

Mr. Bennet was prevented replying by the entrance of the footman with a note for Master Bennet; it came from Netherfield, and the servant waited for an answer. Mr. Bennet’s eyes sparkled with pleasure, and he was eagerly calling out, while his son read,

“Well, Joe, who is it from? What is it about? What does she say? Well, Joe, make haste and tell us; make haste, my love.”

“It is from Master Bingley,” said Joe, and then read it aloud.

“MY DEAR FRIEND,—

“If you are not so compassionate as to dine to-day with Luke and me, we shall be in danger of hating each other for the rest of our lives, for a whole day’s tete-a-tete between two men can never end without a quarrel. Come as soon as you can on receipt of this. My sister and the ladies are to dine with the officers.—Yours ever,

“CHRISTOPHER BINGLEY”

“With the officers!” cried Lance. “I wonder my uncle did not tell us of that.”

“Dining out,” said Mr. Bennet, “that is very unlucky.”

“Can I have the carriage?” said Joe.

“No, my dear, you had better go on horseback, because it seems likely to rain; and then you must stay all night.”

“That would be a good scheme,” said Edelmar, “if you were sure that they would not offer to send him home.”

“Oh! but the ladies will have Mrs. Bingley’s chaise to go to Meryton, and the Hursts have no horses to theirs.”

“I had much rather go in the coach.”

“But, my dear, your mother cannot spare the horses, I am sure. They are wanted in the farm, Mrs. Bennet, are they not?”

“They are wanted in the farm much oftener than I can get them.”

“But if you have got them to-day,” said Edelmar, “my father’s purpose will be answered.”

He did at last extort from her mother an acknowledgment that the horses were engaged. Joe was therefore obliged to go on horseback, and his father attended him to the door with many cheerful prognostics of a bad day. His hopes were answered; Joe had not been gone long before it rained hard. His brother’s were uneasy for him, but his father was delighted. The rain continued the whole evening without intermission; Joe certainly could not come back.

“This was a lucky idea of mine, indeed!” said Mr. Bennet more than once, as if the credit of making it rain were all her own. Till the next morning, however, he was not aware of all the felicity of his contrivance. Breakfast was scarcely over when a servant from Netherfield brought the following note for Edelmar:

“MY DEAREST LAMMY,—

“I find myself very unwell this morning, which, I suppose, is to be imputed to my getting wet through yesterday. My kind friends will not hear of my returning till I am better. They insist also on my seeing Mrs. Jones—therefore do not be alarmed if you should hear of hger having been to me—and, excepting a sore throat and headache, there is not much the matter with me.—Yours, etc.”

“Well, my dear,” said Mrs. Bennet, when Edlemar had read the note aloud, “if your son should have a dangerous fit of illness—if he should die, it would be a comfort to know that it was all in pursuit of Mrs. Bingley, and under your orders.”

“Oh! I am not afraid of him dying. People do not die of little trifling colds. He will be taken good care of. As long as he stays there, it is all very well. I would go and see him if I could have the carriage.”

Edelmar, feeling really anxious, was determined to go to him, though the carriage was not to be had; and as he was no horseman, walking was his only alternative. He declared his resolution.

“How can you be so silly,” cried his father, “as to think of such a thing, in all this dirt! You will not be fit to be seen when you get there.”

“I shall be very fit to see Joe—which is all I want.”

“Is this a hint to me, Lammy,” said his mother, “to send for the horses?”

“No, indeed, I do not wish to avoid the walk. The distance is nothing when one has a motive; only three miles. I shall be back by dinner.”

“I admire the activity of your benevolence,” observed Matthew, “but every impulse of feeling should be guided by reason; and, in my opinion, exertion should always be in proportion to what is required.”

“We will go as far as Meryton with you,” said Kalman and Lance. Edelmar accepted their company, and the three young gentlemen set off together.

“If we make haste,” said lance, as they walked along, “perhaps we may see something of Captain Carter before she goes.”

In Meryton they parted; the two youngest repaired to the lodgings of one of the officers’ husbands, and Edelmar continued his walk alone, crossing field after field at a quick pace, jumping over stiles and springing over puddles with impatient activity, and finding himself at last within view of the house, with weary ankles, dirty stockings, and a face glowing with the warmth of exercise.

He was shown into the breakfast-parlour, where all but Joe were assembled, and where his appearance created a great deal of surprise. That he should have walked three miles so early in the day, in such dirty weather, and by himself, was almost incredible to Mr. Hurst and Master Bingley; and Edelamr was convinced that they held him in contempt for it. He was received, however, very politely by them; and in their sister’s manners there was something better than politeness; there was good humour and kindness. Mrs. Darcy said very little, and Mrs. Hurst nothing at all. The former was divided between admiration of the brilliancy which exercise had given to his complexion, and doubt as to the occasion’s justifying his coming so far alone. The latter was thinking only of her breakfast.

His inquiries after his brother were not very favourably answered. Master Bennet had slept ill, and though up, was very feverish, and not well enough to leave his room. Edlemar was glad to be taken to him immediately; and Joe, who had only been withheld by the fear of giving alarm or inconvenience from expressing in him note how much he longed for such a visit, was delighted at his entrance. He was not equal, however, to much conversation, and when Master Bingley left them together, could attempt little besides expressions of gratitude for the extraordinary kindness he was treated with. Edelmar silently attended his.

When breakfast was over they were joined by the brothers; and Edelmar began to like them himself, when he saw how much affection and solicitude they showed for Joe. The apothecary came, and having examined her patient, said, as might be supposed, that he had caught a violent cold, and that they must endeavour to get the better of it; advised him to return to bed, and promised him some draughts. The advice was followed readily, for the feverish symptoms increased, and him head ached acutely. Edelmar did not quit his room for a moment; nor were the other gentlemen often absent; the ladies being out, they had, in fact, nothing to do elsewhere.

When the clock struck three, Edelman felt that he must go, and very unwillingly said so. Master Bingley offered him the carriage, and he only wanted a little pressing to accept it, when Joe testified such concern in parting with him, that Master Bingley was obliged to convert the offer of the chaise to an invitation to remain at Netherfield for the present. Edelmar most thankfully consented, and a servant was dispatched to Longbourn to acquaint the family with his stay and bring back a supply of clothes.

-

Pride and Prejudice: Gender Flipped Chapter Six

Chapter 6

The gentlemen of Longbourn soon waited on those of Netherfield. The visit was soon returned in due form. Master Bennet’s pleasing manners grew on the goodwill of Mr. Hurst and Master Bingley; and though the father was found to be intolerable, and the younger brothers not worth speaking to, a wish of being better acquainted with them was expressed towards the two eldest. By Joe, this attention was received with the greatest pleasure, but Edelmar still saw superciliousness in their treatment of everybody, hardly excepting even her brother, and could not like them; though their kindness to Joe, such as it was, had a value as arising in all probability from the influence of their sister’s admiration. It was generally evident whenever they met, that she did admire him and to him it was equally evident that Joe was yielding to the preference which he had begun to entertain for her from the first, and was in a way to be very much in love; but he considered with pleasure that it was not likely to be discovered by the world in general, since Joe united, with great strength of feeling, a composure of temper and a uniform cheerfulness of manner which would guard his from the suspicions of the impertinent. He mentioned this to his friend Miaster Lucas.

“It may perhaps be pleasant,” replied Craig, “to be able to impose on the public in such a case; but it is sometimes a disadvantage to be so very guarded. If a man conceals his affection with the same skill from the object of it, he may lose the opportunity of fixing her; and it will then be but poor consolation to believe the world equally in the dark. There is so much of gratitude or vanity in almost every attachment, that it is not safe to leave any to itself. We can all begin freely—a slight preference is natural enough; but there are very few of us who have heart enough to be really in love without encouragement. In nine cases out of ten a man had better show more affection than he feels. Bingley likes your brother undoubtedly; but she may never do more than like him, if he does not help her on.”

“But he does help her on, as much as his nature will allow. If I can perceive him regard for her, she must be a simpleton, indeed, not to discover it too.”

“Remember, Edel, that he does not know Joe’s disposition as you do.”

“But if a man is partial to a woman, and does not endeavour to conceal it, she must find it out.”

“Perhaps she must, if she sees enough of him. But, though Bingley and Joe meet tolerably often, it is never for many hours together; and, as they always see each other in large mixed parties, it is impossible that every moment should be employed in conversing together. Joe should therefore make the most of every half-hour in which he can command her attention. When he is secure of her, there will be more leisure for falling in love as much as he chooses.”

“Your plan is a good one,” replied Edelmar, “where nothing is in question but the desire of being well married, and if I were determined to get a rich wife, or any wife, I dare say I should adopt it. But these are not Joe’s feelings; he is not acting by design. As yet, he cannot even be certain of the degree of his own regard nor of its reasonableness. He has known her only a fortnight. He danced four dances with her at Meryton; he saw her one morning at her own house, and has since dined with her in company four times. This is not quite enough to make him understand her character.”

“Not as you represent it. Had he merely dined with her, he might only have discovered whether she had a good appetite; but you must remember that four evenings have also been spent together—and four evenings may do a great deal.”

“Yes; these four evenings have enabled them to ascertain that they both like Vingt-un better than Commerce; but with respect to any other leading characteristic, I do not imagine that much has been unfolded.”

“Well,” said Craig, “I wish Joe success with all my heart; and if he were married to her to-morrow, I should think he had as good a chance of happiness as if he were to be studying her character for a twelvemonth. Happiness in marriage is entirely a matter of chance. If the dispositions of the parties are ever so well known to each other or ever so similar beforehand, it does not advance their felicity in the least. They always continue to grow sufficiently unlike afterwards to have their share of vexation; and it is better to know as little as possible of the defects of the person with whom you are to pass your life.”

“You make me laugh, Craig; but it is not sound. You know it is not sound, and that you would never act in this way yourself.”

Occupied in observing Mrs. Bingley’s attentions to her brother, Edelmar was far from suspecting that he was himself becoming an object of some interest in the eyes of her friend. Mrs. Darcy had at first scarcely allowed him to be pretty; she had looked at him without admiration at the ball; and when they next met, she looked at him only to criticise. But no sooner had she made it clear to herself and her friends that he hardly had a good feature in his face, than she began to find it was rendered uncommonly intelligent by the beautiful expression of his dark eyes. To this discovery succeeded some others equally mortifying. Though she had detected with a critical eye more than one failure of perfect symmetry in his form, she was forced to acknowledge his figure to be light and pleasing; and in spite of her asserting that him manners were not those of the fashionable world, she was caught by their easy playfulness. Of this he was perfectly unaware; to him she was only the woman who made herself agreeable nowhere, and who had not thought him handsome enough to dance with.

She began to wish to know more of him, and as a step towards conversing with him herself, attended to his conversation with others. Her doing so drew his notice. It was at Lady Wonda Lucas’s, where a large party were assembled.

“What does Mrs. Darcy mean,” said he to Craig, “by listening to my conversation with Colonel Forster?”

“That is a question which Mrs. Darcy only can answer.”

“But if she does it any more I shall certainly let her know that I see what she is about. She has a very satirical eye, and if I do not begin by being impertinent myself, I shall soon grow afraid of her.”

On her approaching them soon afterwards, though without seeming to have any intention of speaking, Master Lucas defied his friend to mention such a subject to her; which immediately provoking Edelmar to do it, he turned to her and said:

“Did you not think, Mrs. Darcy, that I expressed myself uncommonly well just now, when I was teasing Colonel Forster to give us a ball at Meryton?”

“With great energy; but it is always a subject which makes a gentleman energetic.”

“You are severe on us.”

“It will be his turn soon to be teased,” said Master Lucas. “I am going to open the instrument, Edel, and you know what follows.”

“You are a very strange creature by way of a friend!—always wanting me to play and sing before anybody and everybody! If my vanity had taken a musical turn, you would have been invaluable; but as it is, I would really rather not sit down before those who must be in the habit of hearing the very best performers.” On Master Lucas’s persevering, however, he added, “Very well, if it must be so, it must.” And gravely glancing at Mrs. Darcy, “There is a fine old saying, which everybody here is of course familiar with: ‘Keep your breath to cool your porridge’; and I shall keep mine to swell my song.”

His performance was pleasing, though by no means capital. After a song or two, and before he could reply to the entreaties of several that he would sing again, he was eagerly succeeded at the instrument by his brother Matthew, who having, in consequence of being the only plain one in the family, worked hard for knowledge and accomplishments, was always impatient for display.

Matthew had neither genius nor taste; and though vanity had given him application, it had given him likewise a pedantic air and conceited manner, which would have injured a higher degree of excellence than he had reached. Edelmar, easy and unaffected, had been listened to with much more pleasure, though not playing half so well; and Matthew, at the end of a long concerto, was glad to purchase praise and gratitude by Scotch and Irish airs, at the request of his younger brothers, who, with some of the Lucases, and two or three officers, joined eagerly in dancing at one end of the room.

Mrs. Darcy stood near them in silent indignation at such a mode of passing the evening, to the exclusion of all conversation, and was too much engrossed by her thoughts to perceive that Lady Wonda Lucas was her neighbour, till Lady Wonda thus began:

“What a charming amusement for young people this is, Mrs. Darcy! There is nothing like dancing after all. I consider it as one of the first refinements of polished society.”

“Certainly, mad’am; and it has the advantage also of being in vogue amongst the less polished societies of the world. Every savage can dance.”

Lady William only smiled. “Your friend performs delightfully,” she continued after a pause, on seeing Bingley join the group; “and I doubt not that you are an adept in the science yourself, Mrs. Darcy.”

“You saw me dance at Meryton, I believe, mad’am.”

“Yes, indeed, and received no inconsiderable pleasure from the sight. Do you often dance at St. James’s?”

“Never, mad’am.”

“Do you not think it would be a proper compliment to the place?”

“It is a compliment which I never pay to any place if I can avoid it.”

“You have a house in town, I conclude?”

Mrs. Darcy bowed.

“I had once had some thought of fixing in town myself—for I am fond of superior society; but I did not feel quite certain that the air of London would agree with Sir Lucas.”

She paused in hopes of an answer; but her companion was not disposed to make any; and Edelmar at that instant moving towards them, she was struck with the action of doing a very gallant thing, and called out to him:

“My dear Master Edel, why are you not dancing? Mrs. Darcy, you must allow me to present this young gentleman to you as a very desirable partner. You cannot refuse to dance, I am sure when so much beauty is before you.” And, taking his hand, she would have given it to Mrs. Darcy who, though extremely surprised, was not unwilling to receive it, when he instantly drew back, and said with some discomposure to Lady Wonda:

“Indeed, mad’am, I have not the least intention of dancing. I entreat you not to suppose that I moved this way in order to beg for a partner.”

Mrs. Darcy, with grave propriety, requested to be allowed the honour of his hand, but in vain. Edelmar was determined; nor did Lady Wonda at all shake his purpose by her attempt at persuasion.

“You excel so much in the dance, Master Edel, that it is cruel to deny me the happiness of seeing you; and though this lady dislikes the amusement in general, she can have no objection, I am sure, to oblige us for one half-hour.”

“Mrs. Darcy is all politeness,” said Edelmar, smiling.

“She is, indeed; but, considering the inducement, my dear Master Edel, we cannot wonder at her complaisance—for who would object to such a partner?”

Edelmar looked archly, and turned away. His resistance had not injured him with the lady, and she was thinking of him with some complacency, when thus accosted by Master Bingley:

“I can guess the subject of your reverie.”

“I should imagine not.”

“You are considering how insupportable it would be to pass many evenings in this manner—in such society; and indeed I am quite of your opinion. I was never more annoyed! The insipidity, and yet the noise—the nothingness, and yet the self-importance of all those people! What would I give to hear your strictures on them!”

“Your conjecture is totally wrong, I assure you. My mind was more agreeably engaged. I have been meditating on the very great pleasure which a pair of fine eyes in the face of a pretty man can bestow.”

Master Bingley immediately fixed his eyes on her face, and desired she would tell him what gentleman had the credit of inspiring such reflections. Mrs. Darcy replied with great intrepidity:

“Master Edlemar Bennet.”

“Master Eldemar Bennet!” repeated Master Bingley. “I am all astonishment. How long has he been such a favourite?—and pray, when am I to wish you joy?”

“That is exactly the question which I expected you to ask. A gentleman’s imagination is very rapid; it jumps from admiration to love, from love to matrimony, in a moment. I knew you would be wishing me joy.”

“Nay, if you are serious about it, I shall consider the matter is absolutely settled. You will be having a charming father-in-law, indeed; and, of course, he will always be at Pemberley with you.”

She listened to him with perfect indifference while he chose to entertain himself in this manner; and as her composure convinced him that all was safe, his wit flowed long.